Canzano: Bad bet brings out the hypocrisy

MLB cracks down on minor leaguer.

Major League Baseball is doing some interesting things this spring in an attempt to improve the game.

Shift bans, pitch clocks and pick-off limits, among them. But what the league needs most is a dose of common sense.

Peter Bayer is a minor league pitcher. He played his college ball at Cal Poly Pomona. During the onset of the pandemic in 2020, baseball left a sea of minor league players unemployed. Contracts were suspended. Benefits stopped. So did income.

Baseball used the break after the 2019 season to restructure its entire minor league system, eliminating 42 franchises and two minor-league classifications. Minor League Baseball went out of business in 2020, essentially.

During the work stoppage, select players received $400 a week from the MLB clubs to help make ends meet, but a lot of them did not. A few retired. Some others picked up side hustles. The Wall Street Journal wrote about a Triple-A pitcher named James Naile, who worked part-time as a landscaper. Another minor-league player went to work for UPS, another drove for Door Dash, and a number of others were told by MLB to apply for unemployment.

Bayer did something else while he was “not” a professional baseball player in the summer of 2020. He made a mistake. Bayer signed up for a legal sports wagering app in Colorado and placed modest bets on roughly 30 MLB games.

He didn’t play in the games.

He didn’t coach them.

He wasn’t around the teams. In fact, Bayer was collecting unemployment.

“My entire life, I’ve spent the summers playing baseball and without competing and playing, I did not know what to do with myself,” he said.

In early 2021, the Cincinnati Reds signed Bayer to a contract. He was finally employed again and started working out in preparation for spring training. A few weeks later, the commissioner’s office called and informed Bayer that he was under investigation and suspended immediately because he’d wagered on MLB games.

Gambling while unemployed isn’t wise. But it’s not a crime. MLB, though, has strict rules that forbid wagering for players under contract. Rule 21(d) says that players, umpires and club or league officials who bet on baseball shall be suspended for a year.

Also, it further reads: “Any player, umpire, or Club or League official or employee, who shall bet any sum whatsoever upon any baseball game in connection with which the bettor has a duty to perform, shall be declared permanently ineligible.”

Bayer didn’t have a duty to perform. He wasn’t an umpire, a club official, or even under contract. Still, he owned his actions. He apologized. He met with a psychologist upon request from MLB and talked with investigators. He was told to apply for reinstatement after the 2022 World Series. But MLB informed Bayer this week that he’s also suspended for the entire 2023 season.

“I understand that I broke a rule and there is consequences to my actions but this has been way too extensive,” he said.

What Bayer got for placing legal wagers is a stiffer punishment than MLB has doled out for sexual violence, domestic abuse and performance-enhancing drugs. He’s facing his third full season on the ineligible list. Wrap your head around that.

The message from MLB is troubling. A player can strangle a woman and be back on the diamond in no time. He can do drugs and find a path back to the dugout. He can steal signs, trample ethics, waltz off with a World Series championship and face no real punishment. But if you’re an unemployed minor leaguer and place a legal wager on a baseball game, you’re all out of luck.

Bayer acknowledges what he did was wrong. Turns out, he got outed after he wrote an email to the Colorado gaming commission, inquiring about a wager he made on a soccer match. The gaming commissioner did some research on his employment history and alerted MLB.

“At this point,” Bayer said, “I feel like my baseball career is probably over.”

Last summer, a woman told police in Syracuse that Khalil Lee kicked her, pulled her hair, and put his hands around her throat. He’s under investigation for that alleged crime. But Lee got an invitation to spring training from the Mets.

“We trust the process and will let it run its course,” manager Buck Showalter told reporters. “We’ll prepare him to start the season.”

Pitcher Mike Clevinger is under league investigation for domestic violence, too. The mother of his children has accused him of choking her while she was pregnant. White Sox GM Rick Hahn told reporters that the team’s “only option” is to allow Clevinger to come to camp while waiting for MLB to conclude the inquiry.

“It is solely the discretion of the commissioner to discipline a player,” Hahn said.

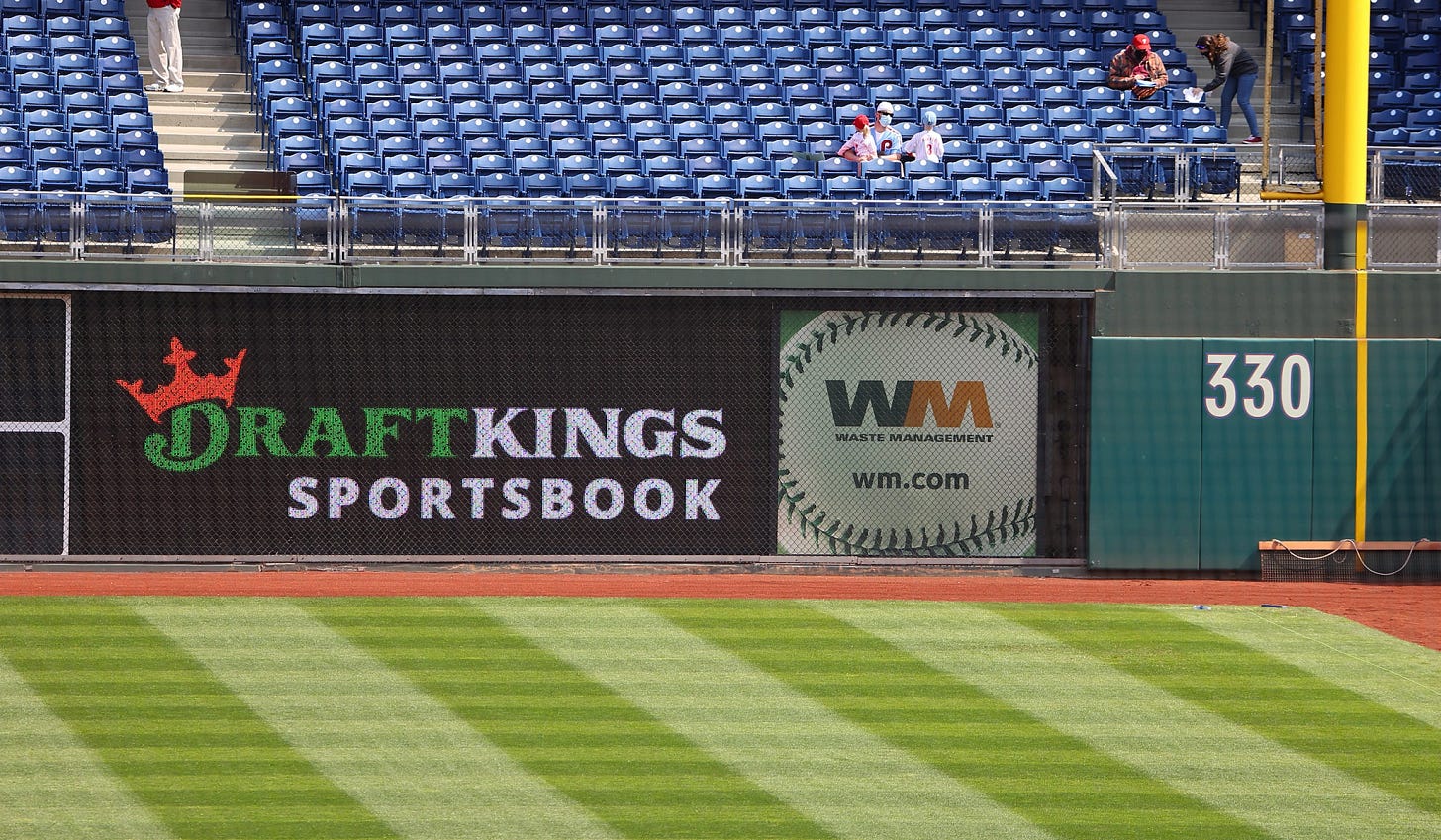

MLB needs to wake up. Trevor Bauer is eligible to play, but a minor leaguer who bet on a game while he wasn’t under contract is enemy of the state? Please. Take a look around MLB ballparks this season. You’ll see signage for a line of legal sports wagering entities, including Bet365 and DraftKings — you know — “the official gaming operator” of Major League Baseball.

Just this offseason, the Reds signed a sponsorship deal that made BetMGM the official gambling partner of the club. In 2022, the Nationals opened a sponsored sportsbook at their home ballpark, becoming the first retail sportsbook connected to a Major League Baseball stadium. But the Single-A pitcher who legally placed a wager while unemployed is on year three of his ban, folks.

“I’m willing to accept punishment for my actions,” Bayer told me on Thursday, “but I don’t believe what I did should have resulted in that kind of penalty.”

Looks to me like Bayer’s biggest crime was that he wasn’t a better player.

I get it.

MLB wants us to believe it takes gambling seriously. It should. It’s serious stuff. Nobody wants the integrity of the game compromised, but MLB is out in left field on this one.

I appreciate all who read, support, subscribe and share this new, independent, endeavor with friends and families. If you’re not already a “paid” subscriber, please consider a subscription or a gift subscription for someone else:

The punishment should fit the crime. In this case, it obviously does not.

I just don’t get how a player can still play after a domestic dispute but an unemployed player bets on some games and is ostracized by the league.