Canzano: The legend of Wilbur Huckle

Friendships, baseball, and bedtime stories.

I grew up on stories about Wilbur Huckle.

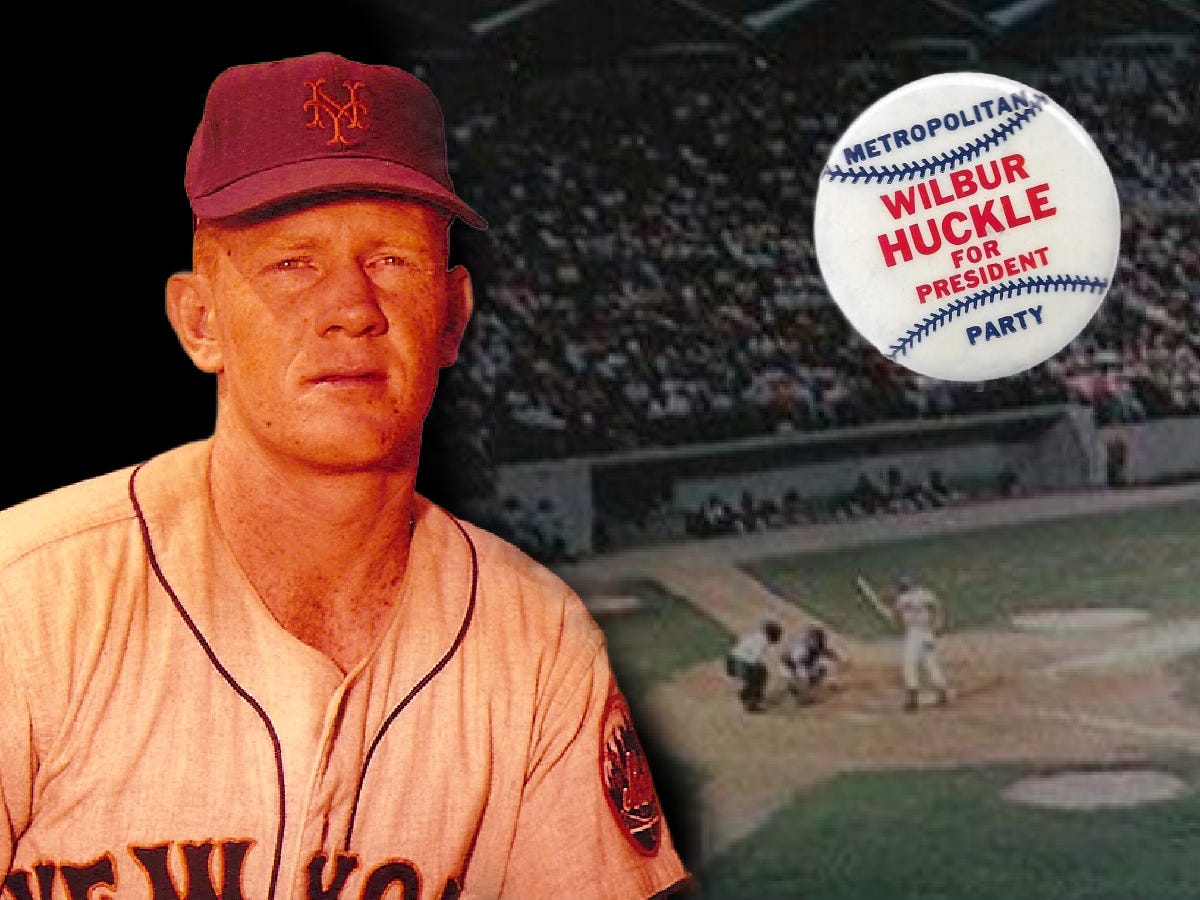

My father and Huckle played baseball together in the New York Mets minor league system. They were both All-Star minor-league infielders and crossed paths in Tidewater in 1969.

The guy had freckles, a full head of red hair, and endless energy. Dad and Huckle hung out together. He’d stand in the middle of the room and jump rope while they watched TV in hotels on road trips. And when he boarded the bus, my father remembers Huckle sometimes walking down the center aisle, making calls like he was an exotic bird in the jungle.

There’s some grainy 8mm film in a closet at my parents’ house that features my father and Huckle on the field in uniform before a Triple-A game. Huckle is holding a bat on the steps of the dugout and pretending to play the saxophone. Then, he pulls out an exploding prank cigarette, sticks it between his lips, lights it, turns to the camera, and waits for the fun.

Only, it never exploded.

It just kept burning.

Tom Seaver, another teammate of Dad’s, drew the room assignment with Huckle on road trips.

Seaver liked to say, “I never saw Wilbur Huckle in our room — at least not awake.”

Minor league games were usually played at night. Huckle would be gone at sunrise and set out on foot. He’d walk around town, get breakfast, immerse himself in the city, and when the local sporting goods stores opened for business, Huckle would be there.

“I think he saw every sporting goods store in every minor league town,” my father said.

Dad says Huckle showed up early to the ballpark for batting practice. He liked to take extra swings and enlisted my father to go with him. Also, Huckle was always the first player to shower and dress after games. He’d beeline from the dugout to the locker room.

Major Kerby Farrell was a long-time minor league manager and coach. My father said Farrell was particularly ticked off after a loss. The team had dropped nine or 10 games in a row. So Farrell rushed into the locker room, blocked the path to the showers, and announced: “Nobody takes a shower until I’m finished talking!”

It grew quiet.

The players stood still.

A moment later, Huckle appeared directly behind Farrell, fresh out of the showers, soaking wet, with a towel wrapped around his waist. The room busted up.

Jon Matlack was a promising pitching prospect in the Mets organization in the 1960s. He went on to become a three-time All-Star in the big leagues. One of my father’s favorite Huckle stories involves Matlack’s development in Triple-A.

The pitcher was struggling with pitching inside. Manager Clyde McCullough, another legendary figure from my childhood, hatched the idea to have Matlack condition himself by practicing brushing back and hitting opposing hitters.

Guess who volunteered to let Matlack throw at him?

Huckle stood in the batter’s box, crowding the plate. Players gathered around to observe. Matlack took the ball and repeatedly knocked Huckle down (or even hit him) with pitches — over and over.

“That lasted a long time,” my father said.

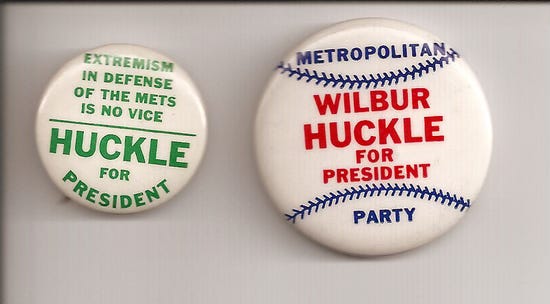

Huckle ran for United States President in 1964. Did you know that? New York Mets fans adopted the loveable Huckle and launched a fictitious campaign in front of that election. The organizers even created a couple of political buttons. To this day, Huckle doesn’t know why fans picked him, but I know. He was a character with an amazing personality and memorable first and last name.

The eccentric and unforgettable “Wilbur Huckle” was the perfect candidate to pit against a conservative from Arizona named Barry Goldwater.

Huckle is still alive. My father got a call from him out of the blue a couple of weeks ago. He’s 83 and living in Texas, where he’s a wildlife land manager who takes care of 600 acres for the state.

The old baseball teammates have talked twice on the phone in the last two weeks. The most recent spanned an hour. Huckle and my father talked, laughed, and reminded each other of forgotten stories. They also remembered old friends and baseball teammates who had died.

Huckle made it to the big leagues as a September call-up in 1963. He never got in a game, though. He holds the distinction of appearing on the Mets’ major league roster, but he never got a plate appearance, ran the bases, or even took the field for a single out.

Casey Stengel, the manager of a dismal team that finished the season 51-111, refused to put him in. After I heard that, I stopped being a Stengel fan.

My father and Huckle talked about that this week. Huckle told Dad that when he walked through the entrance to the Polo Grounds for his first big league batting practice in 1963, he encountered Willie Mays in the outfield.

He must have been starstruck. But Mays saw the wide-eyed Huckle standing on the outfield grass, called him “rook,” and shook his hand. Also, Duke Snider, who was with the Mets at the time, saw Huckle, walked across the clubhouse, and introduced himself. I always liked those guys. I like them even more now.

My father is a wonderful storyteller. I think he got that from his father, who understood the importance of timing and cadence. At bedtime, when I was a kid, my dad filled the space before I closed my eyes with tales from his professional baseball career.

Dad hit a home run off the legendary Luis Tiant once. He played with Seaver, Nolan Ryan, and against so many others. My father once got in a fistfight with Carlton Fisk, who slid aggressively into second base trying to break up a double play.

One time, in spring training, my father and a teammate rented two fishing poles for the day and were casting off a pier in Florida. They could barely afford to rent the equipment on a minor-league baseball salary, and at one point, one of the rented poles went overboard into the sea and was lost.

It was a troubling development.

A few casts later, an unthinkable thing happened. My father was reeling in when he felt a tug on the line. He’d caught something. Not a fish, it turns out. He and his teammate were delighted to find they’d caught that lost fishing pole.

Huckle wasn’t there that day. Maybe he was riding his bicycle around St. Petersburg, Fla., visiting sporting goods stores, or watching television while jumping rope. Or maybe he was buying a pack of exploding cigarettes.

I’m glad Huckle picked up the phone and called my father. My dad hasn’t stopped talking about hearing from his old friend. Maybe it will move you to pick up the phone and make a call to an old friend today.

I grew up hearing stories about Wilbur Huckle.

I love that he’s still out there.

I appreciate all who support, subscribe, and share this independent endeavor with friends and family. If you haven’t already — please consider subscribing and gifting a subscription to someone who would enjoy it.

This is an independent reader-supported project with both free and paid subscriptions. Those who opt for the paid edition are providing vital assistance to bolster my independent coverage.

Your father taught you well how to tell stories and we’re all the beneficiaries of his teaching skill.

Wonderful story. Left me wanting more about your Dad's baseball career, too.

Growing up in a minor league town, Portland, left me with great memories of many players who didn't quite make it beyond AAA. I especially appreciate stories that feature those guys.