Canzano: Jackie Robinson and a bedtime story worth remembering

My father used to tell me a bedtime story...

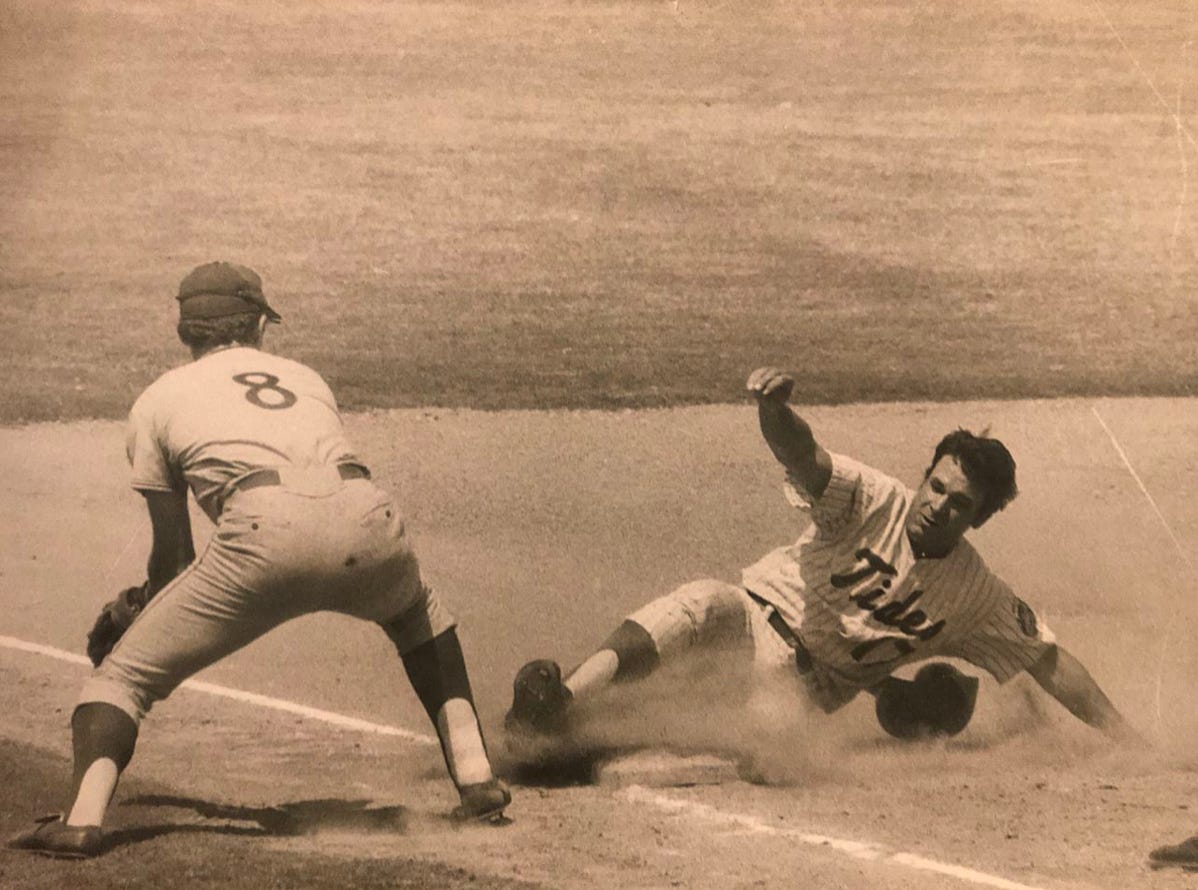

My father was a career minor-league ballplayer. The bedtime stories were wild. I fell asleep to dad telling me about the time he hit a home run off Luis Tiant. Or the game in which he squared off near second base with Carlton Fisk.

Dad was a shortstop in Triple-A at the time. Fisk was on first base when a ground ball was hit. The Hall of Fame catcher raced toward second and slid past the bag — spikes high — trying to break up a double play. My father jumped, completed the throw, but reached down and slapped the sliding Fisk across the face with his glove.

Punches were thrown.

Benches cleared.

There’s an old newspaper clipping someplace featuring a photo of dad, his jersey buttons ripped off, wrestling with Fisk on the infield dirt.

I love that tale. But the bedtime story I thought about the most over the years was set in a diner in 1965 in Lexington, North Carolina. Dad was playing at the time for Single-A Greenville, an affiliate of the New York Mets. His best friend on the team was an outfielder named Curtis Brown, who rose through the minors and eventually played a single game in the big leagues.

The team bus pulled into the parking lot of that diner in 1965 for lunch. The players shuffled in and were seated. My father sat beside Brown. Then, a waitress appeared, looked at the color of Brown’s skin and asked, “Are you Indian?”

“No,” Brown said, “I’m a Negro.”

“I can’t serve you,” she said.

Today marks the 75th anniversary of Jackie Robinson’s debut in the Major Leagues. He’ll be celebrated, honored and talked about. But the scene with my father and his teammates in that restaurant came a couple of decades after baseball’s integration.

Brown grew up in California. So did my father. They were just teenagers in 1965, chasing a professional baseball career, busing across the Carolinas. Along the way they got a sobering introduction to a part of the country that was still woefully lost amid the Civil Rights movement.

I interviewed historian and filmmaker Ken Burns about Jackie Robinson and the significance of April 15, 1947. He reminded me that when Robinson walked out to first base for the Dodgers and broke baseball’s color barrier, Martin Luther King Jr. was only a junior in college.

The United States military hadn’t yet been integrated.

Brown vs. The Board of Education hadn’t yet outlawed segregation in schools.

“He was a Freedom Rider before Freedom Riders… it’s not just a great story in sports, it’s not just a great story in American history… this is a great human story,” Burns said.

By the time I got to high school I knew Robinson’s story cold. I’d read it, done book reports on it in elementary school, and admired and celebrated his courage. When it came time to pick a jersey number I asked for and received No. 42.

I loved that number.

Still do.

Today, every MLB player will wear it. Also, UCLA — Robinson’s alma mater — will play Stanford in a stadium now named after him. The Bruins will hand out “42” T-shirts to the first 1,000 fans. And there’s something about all of this that feels just.

That diner scene crosses my mind often.

The waitress, my dad recounted, was hushed in her tone when she urged Brown to say he was Native American. He refused to play along. He was black. She told him he’d have to sit on the bus and wait. His teammates could order and bring food to him. But it’s what the team did next that I remember most.

“We walked out,” dad said.

Most of Curtis Brown’s teammates set their menus aside, rose to their feet, and got back on the bus, still hungry. They’d wait for the next town and try again. A few of the teammates who grew up in the South stayed behind and ate. In my young mind, that story always underscored the importance of action.

You’re either in the diner or on the bus.

You either stand with Curtis Brown or you don’t.

I will never forget my father’s voice rising and his eyes dancing when he asked, “Did I ever tell you about the time I took Luis Tiant downtown?” Or hearing stories about the spring training he spent playing shortstop behind Nolan Ryan and Tom Seaver. And that scrap with Fisk must have really been something to see.

But the greatest bedtime story dad ever told me is about the lunch he never ate.

It still feeds me today.

Thanks for being here. I appreciate all who have supported, subscribed and shared this new independent endeavor with friends and family. If you haven’t already — please consider subscribing.

Wow, I choked up with the diner story. I remember as a kid with my parents and 5 siblings seated at a Denny ‘s or Sambo’s ( remember?) we could not get the waitress to take our order. My dad was an internee and military veteran who was part of the 442nd . Military intelligence. Everyone else around us had their food. I ate the sugar packets and then my Mom said “ let’s go” I didn’t understand til i was much older. It was my maternal grandmother who when I met her for the first time when I was 12. She said to my face, keep those Jap kids away from me. I didn’t like that woman and never saw her again after my sisters wedding. You see, it isn’t just black and white.

We were a mixed race family in the 60’s. The lesson we learned is to treat people as you would like to be treated.

Let’s all get on the bus!

A delightful and insightful story John and so well written. You have a gift that this new venture allows to come out and thus I hope it goes very well for you