Canzano: "I'm lucky to be talking to you."

A Memorial Day conversation with a Navy man.

I have never been on a military patrol boat. Never seen the rivers and canals of Vietnam. Especially not during a war. I wasn’t even born when Doug Bomarito signed on for a second tour and was charged with leading riverboats deep into enemy territory.

It’s been said that the Viet Cong guerillas and the North Vietnamese Army were both everywhere — and nowhere — at the same time. As Bomarito told me on Sunday: “They were smart foes. They’d been watching what we were doing and set us up.”

Bomarito is a Navy man. He got his commission from the Naval Academy in the Class of 1968. He’d served on a destroyer off the Vietnamese coast early in the Vietnam War. But in the fall of 1969, the former college baseball player volunteered for a closer look. He was put in charge of patrol boats, navigating dangerous waterways of the Mekong River in what would go down as a costly war.

“I’m lucky to be talking to you,” Bomarito told me.

He participated in 75 riverboat patrols in six months of duty. His final mission launched shortly after dinner one evening in February of 1970. The enemy had been using the waterways to move supplies to the Ho Chi Minh Trail. Bomarito’s team was charged with going out at night and intercepting the supply transfers.

Was he scared?

I asked him on Sunday.

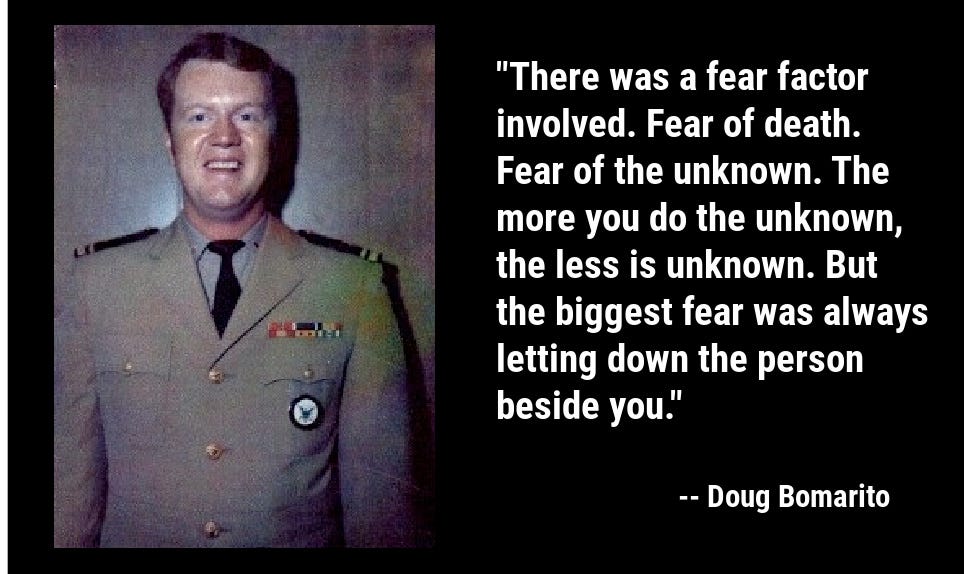

“There was a fear factor involved,” Bomarito told me. “Fear of death. Fear of the unknown. The more you do the unknown, the less is unknown. But the biggest fear was always letting down the person beside you.”

The sky was still light when his boat got ambushed and hit with a shower of bullets and B40 rockets. The sides of Bomarito’s fiberglass boat burned and melted down to water level. Bomarito, now 79, would be sliced by shrapnel on both sides of his rib cage, under his arms, and across his lower back. He and another injured crew member managed to beach their boat, before being evacuated by a Navy SEAWOLF helicopter.

It’s Memorial Day. Bomarito will start his day with a bowl of yogurt and berries. He’ll drive from his home in Lake Oswego toward Washington Park. Once there, he and some other military veterans will arrive at the Oregon Vietnam Veterans Memorial where 10 volunteers will read the names of the 808 military members from the state who were killed in action during the war.

“20 others are still MIA,” Bomarito said.

They’ll read those names, too. The event begins at 10 a.m. It’s part of a Memorial Day tradition born from the efforts of a small group of local veterans who wanted to create a living memorial to honor those who were lost.

Bomarito survived the Vietnam War. He was awarded a Bronze Star and a Purple Heart. After his recovery from several surgeries and the loss of a piece of his intestine, he moved to Portland, went to law school, got married, had children, and made a life. But a military mission never ends, particularly when so many don’t make it home.

Bomarito was instrumental in the creation and dedication of the memorial site. Maybe because he came so close to death. Or perhaps because his biggest fear remains letting down those who served beside him.

“We’ve been honored to do this,” Bomarito said. “There are five or six of us guys who go up there and make sure the landscape of the memorial is what it should be.”

They clean the hard structures.

They pick weeds.

“We make sure it’s ready,” Bomarito said, “not just for Memorial Day, but for every day.”

I spoke with Bomarito for a spell on Sunday. We talked about his late wife, Jean, who died five years ago, and his children, and grandchildren. I asked him what it was like to play baseball at the Naval Academy. Bomarito’s coach, a man named Joe Duff, was a legend in Annapolis. He was a World War II veteran who led the Navy baseball program for 32 years and coached players such as Roger Staubach.

“Duff was a no-nonsense guy,” Bomarito told me, “but he was very fair.”

We talked about the riverboats and the casualties in Vietnam. It was a costly and complex war, doomed from the beginning with poor military strategy and an underestimated enemy. Bomarito, born in Detroit, chose the Pacific Northwest as his home after the war because he’d made a stopover in Bremerton, Wash.

“It was such a beautiful place,” he said.

I don’t know how you’ll celebrate Memorial Day. But Bomarito will travel to the memorial site and listen to volunteers take shifts reading the names of soldiers who gave their lives for our country. There will be a flyover by a military aircraft, a gun salute, and a flag presentation.

Jud Blakely, a Sunset High and Oregon State graduate, will give a speech. Blakely, a Marine, served in Vietnam and remains one of Bomarito’s closest friends. Then, the group will go to a private lunch event at The Old Spaghetti Factory.

Simple, significant, stuff.

I woke on Memorial Day thinking about those who sacrificed so much. Not just soldiers killed in action, but also, so many loved ones left behind. I thanked Bomarito for his service, not just in Vietnam, but for his work over the last few decades honoring the memory of others.

Before we hung up, he told me something I’ll never forget. The landscape architect who designed the memorial site planted flowers that bloom twice a year — November and May. It lines up with Veteran’s Day and Memorial Day.

Said Bomarito: “It’s something to see.”

Thank you for reading. I appreciate all who have supported, subscribed, and shared my new independent endeavor with friends and family in recent months. If you haven’t already — please consider subscribing.

As someone born in 1956, I remember the Vietnam War as portrayed on network TV news every night (Walter Cronkite, et al). But I had never seen the riverboat troops that had to go deep into jungles in pursuit of the Viet Cong until I saw the movie "Apocalypse Now" which portrayed those missions, seemingly very accurately. Wow, was that intense for those servicemen who had the unenviable job of carrying out those missions. I have nothing but respect for Doug Bomarito and all his comrades. My own father, Donald McMorris, who passed away last October at 93, was a young Army Lieutenant who graduated at Oregon State in 1952. He had joined ROTC as a freshman and was a top officer candidate. My dad was assigned to an artillery group and trained in Ft Lewis and at the artillery ranges in Ft Sill in Oklahoma with the top performance of any artillery officer in his class. By the end of 1952 he was sent to Korea to fight in the war. My dad was great with a slide rule and able to calculate the proper trajectory of the big guns on the fly and later under fire in North Korea when he was involved in several campaigns, including Triangle Hill, which was the peak event (in terms of violence) of that war. My dad obviously survived Korea, but many of his friends there didn't. I had the good fortune to sponsor my dad on a trip to Washington DC on an Oregon (Mid-Valley) Honor Flight. Anyone who has a relative who served should take advantage and do the same. It is life altering both for the serviceman/woman and for the sponsor.

I served during the Vietnam era but was never sent so from my perspective it wasn’t just poor military leadership in some cases but mostly governmental interference. Stupid ROE and changing policy from month to month. I didn’t realize that at the time but as the years have gone by there are more facts being revealed. Our government let us down.