Canzano: A sensei never stops teaching

What can we learn from 'regular' folks?

I wrote a column about a Japanese sensei years ago. A judo instructor named Jim Onchi died. He was laid to rest in a burial plot at Lincoln Memorial Park in Portland.

I missed the guy’s entire life. I’m ashamed of that. His struggles, trials, successes, and accomplishments over 94 years were lost to me until Onchi died in 2013. I received a call from Sho Dozono, a family friend of Onchi, who attended the funeral, kept checking the newspaper, and wondered if anyone was going to write about him.

“Do you know how rare it is to be a ninth-degree black belt?” Dozono asked me.

Onchi trained and taught judo for more than 75 years. He was recognized by the Emperor of Japan for his commitment to the craft. I called the United States Judo Association for some additional context.

Me: “Hello, I would like to become a ninth-degree black belt. I’m a beginner; how long will that take?”

The person on the other end: (Laughter).

Onchi was a master in his sport. He became an instructor in 1955 and continued to teach judo to area children into his early 90s. His kidneys failed and his bones ached. When he couldn’t drive anymore, Onchi rode a city bus to Peninsula Park Community Center for weekly practices, almost right up until his death.

His son, Gary, told me: “He’d just find a way to get there and get home. He believed young people needed judo.”

Are you tracking the latest with the LeBron James drama? He’s in an escalating public feud with TV sports commentator Stephen A. Smith. They’re beefing and throwing barbs. The scene is mindlessly amusing and sad at the same time.

Smith is a skilled antagonist and unapologetic self-promoter who knows what he’s doing in front of a camera. James grew up as a generational superstar in his sport. He was so gifted with a basketball that he skipped college, signed a $90 million sneaker deal with Nike, and went straight to the pros.

I’m not taking a side today. The feud is self-important and a grotesque statement about our society. John Updike captured it beautifully when he wrote: “Celebrity is a mask that eats into the face. As soon as one is aware of being ‘somebody’ to be watched and listened to with extra interest, input ceases, and the performer goes blind and deaf in his overanimation.”

That’s it, isn’t it?

For both sides?

Out of vanity and the drive to play basketball alongside his kid in the NBA, LeBron broke the cardinal rule of parenting — he stopped doing it. He leveraged his fame and ushered his poor son, Bronny, into a situation he wasn’t prepared for. He pushed the kid into the most challenging basketball league on the planet. The result has been ugly. The sports world can’t unsee it. And Smith is doing what he’s always done — pouring a can of gasoline on the wreckage and lighting a match.

The entire drama makes me think about that old sensei. He lived a quiet, simple life that mattered in his community. He was a husband, a father, and a soldier in the United States Army. Nobody on national television said a word about it. The guy just woke up every day and lived a good life.

I missed Onchi’s funeral by a couple of weeks. When I arrived at his gravesite at the cemetery in Southeast Portland, what was once a large flower arrangement at his funeral was just a pile of stems and leaves at the foot of his headstone. Strips of grass sod placed over the soil at the burial site hadn’t taken root yet.

The day I was there, a graveside worker was setting up a canopy for a service a few rows away. He set up a line of green folding chairs beneath it. Then, the flower arrangements showed up. I remember thinking the cemetery was filled with good people who lived good lives. We sure like to tidy up at the end, don’t we?

Onchi was a high-school drop-out. He left school at 14 after his father died. There was work to do and the family had a 30-acre farm in Gresham. Maybe a year later, Onchi stumbled upon a clinic run by the founder of judo (Jigoro Kano).

He was hooked.

In 1941, Japan bombed Pearl Harbor. The war flipped the world upside down for Japanese Americans. US officials ordered Onchi’s family and other Japanese families off their property. They were sent to what was the Multnomah County fairgrounds. Then, transferred to the livestock exposition grounds in Portland, then internment camps in California, Arkansas, and Wyoming, where they were imprisoned until 1945.

Onchi didn’t go to the internment camps. He was already enlisted in the US Army. His commanders discovered that he could teach judo to fellow soldiers. It helped with hand-to-hand combat. Onchi rose to the rank of corporal, then platoon sergeant, and then master sergeant. He would earn a Congressional Gold Medal. Still, the letters he wrote to his loved ones were delivered to internment camps.

“He didn’t talk much about any of that,” said Gary Onchi. “In that era, everything was in turmoil. Everybody was shipped out. When my dad encountered obstacles or trouble, he would just find a way to work through it.”

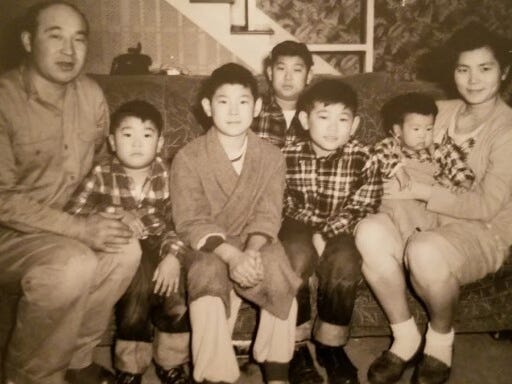

The camps provided Jim Onchi with one good thing — the love of his life. He was visiting his family on a three-day pass to an internment camp in Jerome, Ark., in 1943 when he met a 20-year-old woman named Fumiko. They fell in love, got married, and had five sons.

“I think he’d heard from family that our mom was there,” Gary told me. “I don’t think it was an accident he came there on a furlough.”

Each of their sons attended the same high school (Benson High) and graduated from Portland State. They learned judo and the construction business from their father, and have families of their own now.

Boxing is violent. Its punches are designed to pummel the body and brain of the other fighter. The objective is to strike the opposition so hard and frequently in the skull that it causes a loss of consciousness and a knockout on the canvas.

“Judo” is translated as “gentle way” in Japanese.

It’s an artful persuasion to the mat.

Jim Onchi didn’t just teach judo — he lived it. He overcame adversity, fought in a world war, came home to Portland to live in low-income housing, and somehow found a way to make a wonderful life. So why does the world spend so much time focused on stuff like the LeBron vs. Smith bout? And so little time is spent on people such as Onchi? Just asking. Because the guy got to the end of life, age 94, looking like a world champion human being, and the local sports columnist showed up to the funeral two weeks late.

It’s a reminder to me to pay closer attention.

Maybe to you, too.

Onchi raised a wonderful family, built hundreds of homes, and taught judo to children for seven decades. I love writing columns about “regular” people. Maybe you love reading them. But let’s face it, Jim Onchi was anything but “regular.”

He was spectacular, and if it weren’t for his friend reaching out to ask if I was going to write about him, I’d have missed the entire act. It makes me wonder how many other compelling stories are out there, being overshadowed by catfighting noises and this week’s celebrity sports feud.

A sensei died. He was buried. But he’s still teaching.

John, you never cease to amaze me. Your humanity is extraordinary. Your daughters are lucky to have a great role model. Keep writing the stories of the people the world should lift up.

Beautiful, John. It is people like this that sustain our civilization in the face of the strife placed before us by the influential, powerful, and clueless. Well played, Charlie